Physical and online spaces have long been considered separate. But advancing technology is increasingly blurring the line between them. And some, like Anders Grimstad, wonder whether the virtual experience will replace the physical one.

“It might, but I’m not sure that that’s necessarily a bad thing,” Grimstad said. “People can get a lot of good out of meeting virtually because it’s a social place. You can interact, you can talk, you can engage with people.”

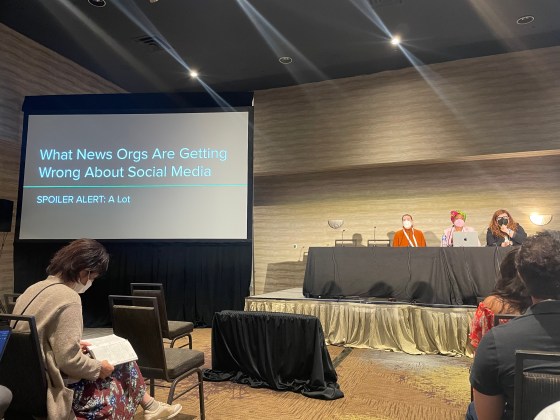

Grimstad is the head of foresight and emerging interfaces at Schibsted, an international media company based in Norway. He laid out how some emerging technologies interact with journalism at the Online News Association’s 2022 conference.

New tech has the potential to further undermine trust in journalists, Grimstad said – but can also provide new ways to connect with people and deliver news to audiences that traditional media is missing.

Grimstad pointed to two broad categories journalists should be watching: synthetic media and spatial experiences.

Synthetic media

Synthetic media is exactly what it sounds like — artificial content in all its forms, including text, image and sound.

Text

Large language models are artificial intelligence (AI) systems that can understand and create text. They’re becoming more accurate and used for tasks like writing copy.

Grimstad said these models can change content into more engaging forms depending on the audience. For example, he said a team at Schibsted built a code that took complex weather data and churned out easy-to-read text about what to expect for the day’s weather. When rain was expected, it added an umbrella emoji.

Outside of the daily weather, Grimstad said large language models have implications for reaching new audiences, especially ones that journalists are currently struggling to connect with, like young people.

“We write articles that are way too long, that are not engaging them in the right way,” he said. “That is a tool, short-term, that can be very useful for us to improve our reach.”

Image

One of the memes that flooded social media earlier this year was from DALL-E mini, an AI platform that generates images from any text prompt users input. (This does mean any image — some DALL-E mini prompts include “babies doing parkour” and “roomba in the Mariana Trench.”)

Though it’s often used for fun, DALL-E mini is a powerful code that’s been trained to find patterns between images and text descriptions. That’s how it creates visuals for even the wackiest prompt.

Image AI systems can be powerful creative tools, Grimstad explained. Some have features like editing and image completion. If you’ve wondered what could be going on outside of the frame of a famous painting or photograph, an AI system can tell you.

Visual synthesis has implications for art and photojournalism, he added. It opens up new avenues for creative projects but also raises complicated questions about intellectual property — if a piece of art is created by an algorithm, who gets the credit?

Audio

Audio synthesis is also getting more sophisticated. Text-to-speech technology has existed for years and continues to get more accurate, but new tools are pushing new boundaries — for example, some can train themselves to mimic the specific sound of a voice.

Grimstad said audio tools might enable users to experience content across different devices and media. It could also change the podcast market when all content is immediately available in audio format, and improve accessibility for people who need audio.

There are tools that combine all three fields of synthetic media. Descript is an all-in-one platform with audio, video and transcript editing — it can delete filler words from audio recordings with a single click.

And all three have implications for newsrooms, especially in the realm of misinformation, Grimstad said. AI tools can create deepfakes — audio or videos of people saying or doing things they didn’t actually do — that look scarily realistic.

Spatial experiences

Spatial experience technology is based on physical spaces — specifically, digital spaces designed to mimic or augment physical spaces.

The metaverse and digital spaces

While its exact definition is subject to debate, the goal of the much-touted metaverse is to be a digital space where people can spend time using virtual reality. Some envision it as a joining of people’s physical and digital lives.

Digital identities for people and things are going to be crucial for identifying what’s truthful in a digital reality, Grimstad said. Tech companies would need to implement laws to track these identities, he warned.

The metaverse is a high-profile project being developed by Facebook’s parent company, Meta, and it gets a lot of attention. But Grimstad said the language used for it was similar to how people talked about the internet at its inception and cautioned against journalists being swept up in the potential of virtual reality.

“Nobody really has any idea how it will actually play out. So my argument for this is don’t spend too much time on the visions of what the metaverse could do — spend time on technologies that are being developed to support this,” he said.

Capture and creation

The cost and effort that goes into creating 3D experiences is decreasing rapidly. Grimstad pointed to complex, detailed 3D maps of major cities as an example of how spatial technology is advancing. Motion capture and virtual reality headsets are making it easier to enter digital spaces, and tech companies are developing mobile extended reality for phones.

3D has the potential to drastically change the way journalists tell stories. Readers could not only read about something — like an event or a conflict zone — but walk through it and see it with their own eyes. Journalists would also need to consider how they fit into these digital spaces, and how to cover events that happen in them.

The fact that new tech will continue to develop and change our world is a certainty, Grimstad said. It’s going to change the way that consumers interact with news and other content, and their attitudes toward the media.

But how exactly everything will play out isn’t as sure, and depends on what happens now. Regulations of digital spaces and how newsrooms implement technology will make a difference whether we lose trust in the media or have a bolstered appreciation for journalism, Grimstad said.

Grimstad outlined two views of where journalists can go from here. The first is pessimistic: If journalists fail to adapt and leverage synthetic media, people’s trust in reporters could wane even further. Disparate groups could become even more isolated in the metaverse, which could provide a physical space for echo chambers.

On the other hand, he said technology could aid journalists in helping tell what’s real and what’s fake. Newsrooms could be prepared for a possible shift into digital space and increase the transparency of their reporting. AI could be used to cater more specifically to certain audiences.

“If we want to live in this type of optimistic frame, we will need to do it ourselves,” Grimstad said.

You must be logged in to post a comment.