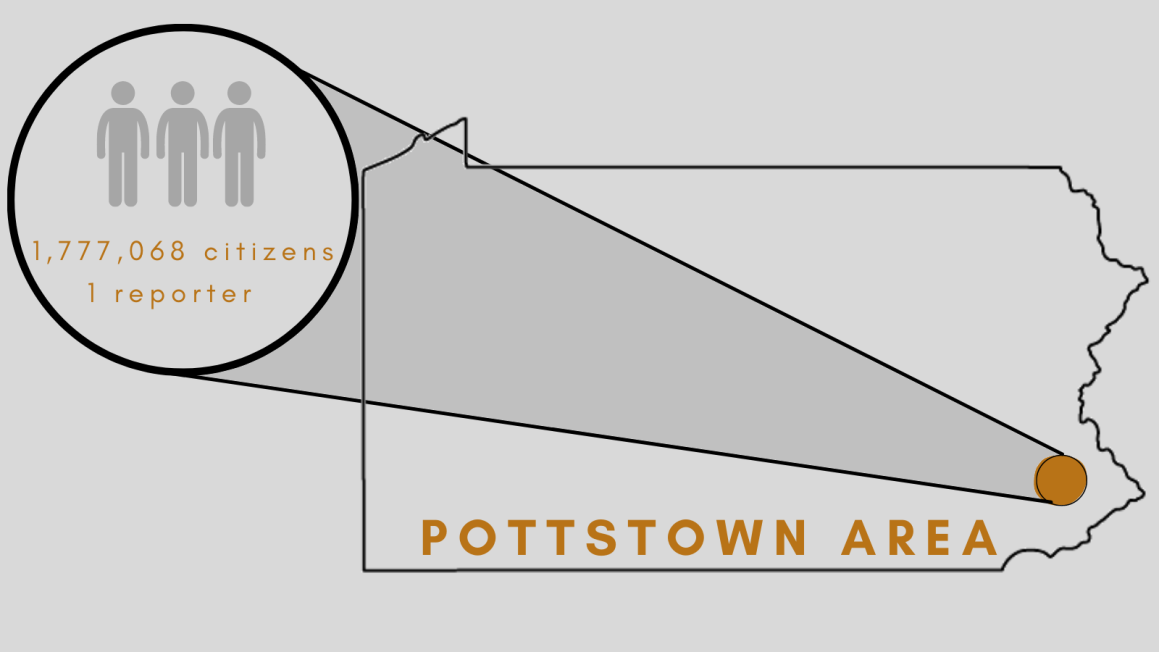

Evan Brandt now works alone in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, to deliver the news to the town and its surrounding areas.

He’s been a reporter at the Mercury for 24 years — watching other media outlets, blogs and radio stations come and go along with reporters. In 1997, Brandt said there were nine reporters at the Mercury in Pottstown. Now he’s the only full-time reporter left in Pottstown.

He spends his day working in his attic after the Mercury’s office building was sold in 2018. Stories pile up on his desk as he tries to get to every one but as a single reporter, it’s nearly impossible.

Brandt doesn’t spend a lot of his time dwelling on the stories he never had the chance to cover because he got too busy. He just has to keep going.

“People don’t know what they don’t know,” Brandt said. “I tried to get everything that came across my desk.”

But Brandt really isn’t alone.

News deserts are common in the United States. According to Poynter, 1,800 communities across the country that had a local news outlet in 2004 didn’t have one at the start of 2020.

Tom Stites, a former New York Times reporter and founder of the Banyan Project, said he believes news deserts begin to form when outlets aren’t covering their own communities. The threshold, according to Stites, is when 60% of people in an area aren’t being reported on.

“If you get discarded, you’re living in a news desert,” Stites said.

Hedge fund ownership of small newspapers can also run community news dry. Stites said he believes many big newspaper chain owners view the journalism industry as a cash grab. As local papers are gasping for air to stay alive, they tend to cater their content more toward the upper echelon who call the shots on funding.

“A newspaper is so much more than news. A newspaper gives you this sense of community, and without that, you might have a loss of pride in your community or loss of connection with your fellow neighbors.”

Nick Mathews, former reporter and doctoral student studying news deserts at University of Minnesota

‘Starving for Information’

The vital nature of a small-town newspaper, these reporters say, became readily apparent during the pandemic. As COVID-19 swept through small communities, people started turning to their local papers for trustworthy information about where to get access to testing sites, where COVID-19 infection clusters were popping up, or simply which restaurants were closed.

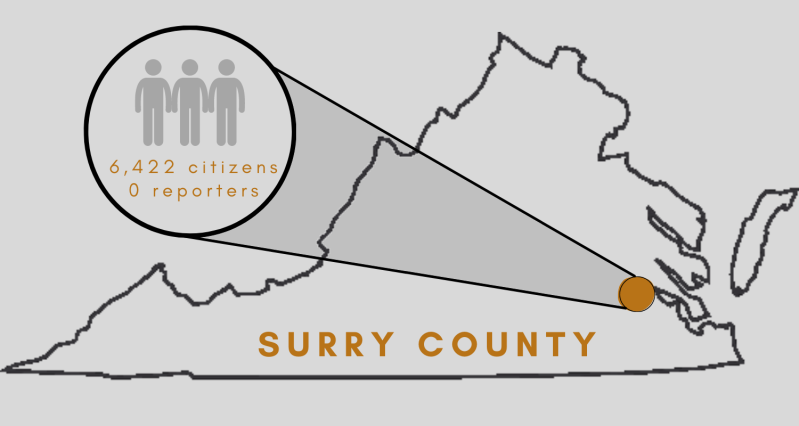

Those living in news deserts were likely to resort to word of mouth and social media to learn about what was happening around them, which is what happened to Surry County, Virginia.

Nick Mathews, a former newspaper reporter and now a Ph.D. student at the University of Minnesota studying news deserts, spent time researching Surry over the past year where the community has no local paper. They said there are no nearby publications that cover the area, either. This led people to take on the job of full-time reporters to scout out information pertinent to keeping them safe in the pandemic.

“People were just starving for local information about it in an area like that. There was a dearth of it, they couldn’t find,” Mathews said.

Citizen journalism — especially when done through Facebook — can potentially lead to misinformation, though. So, even just one newspaper could make a difference, even if its reporters are stretched too thin. In May, Poynter found that 704 local digital news startups had begun across the United States and Canada.

‘Working Harder Than I’ve Ever Worked In My Life’

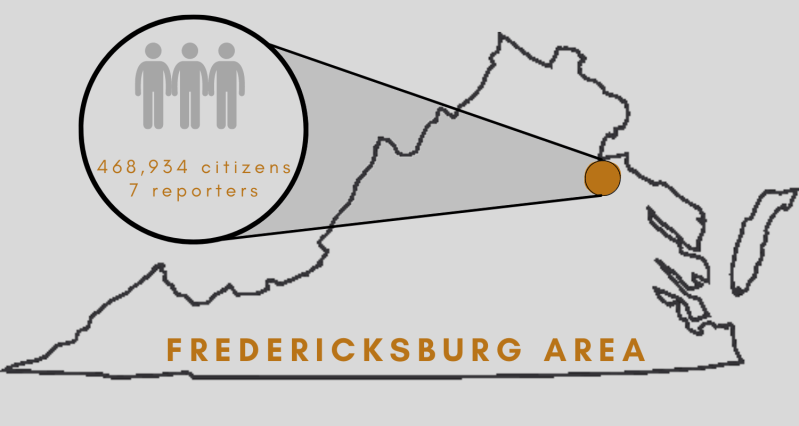

About 120 miles north of Surry County, Cathy Dyson was spending tireless hours in Fredericksburg, Virginia, for the Free-Lance Star. The paper has seven full-time reporters to cover seven counties and two cities in the area.

“I have worked harder in the last 15 months than I have ever worked in my life, and I’ve always been a really productive person, but, you know, you can’t keep up that kind of coverage,” she said.

Dyson called the pandemic an “information deluge” where things were changing hourly, which prompted an influx of urgency from the local community. She received calls and emails nonstop, particularly from older residents, who were confused — especially when the vaccine rollout began.

“People were just distraught,” Dyson said.

Brandt said the pandemic “increased the sense of mission and the sense of thinking” in local journalism. His expertise was in municipal reporting, but he transformed himself into a health reporter to cover everything related to the pandemic. He called COVID-19 “one topic with one hundred facets.”

Like Fredericksburg, the Pottstown community was taking notice of how important local journalism was to their towns, because it wasn’t information they could get just by reading national publications.

“It was literally life saving,” he said.

To Brandt, the community started to appreciate local journalism for the first time in years. For many local papers, including the Mercury and the Free Lance Star, COVID-19 coverage became free to the public because it was so fundamental to people’s health. It didn’t matter if it cost small papers money, reporters had a bigger concern.

Dyson said her editors encouraged their small staff to put everything they had into pandemic related coverage — with little concern about what could happen to the paper afterwards.

“No matter what happens to the paper in three months, six months, a year down the road, we need to give it everything we have so we can look back and say, ‘We gave it our best shot,’” Dyson said, quoting her editor.

But the enthusiasm for local reporting eventually fizzled out in Brandt’s case. He said the Pottstown community has gone back to being unbothered by its local paper.

Dyson, however, said requests continue piling high on her desk to cover more features, events and happenings in the local community. She isn’t sure if it’s from a sparked realization of the importance of local news in Fredericksburg, but she knows she can’t keep moving at breakneck, pandemic speed for much longer.

And as the country begins to emerge from the pandemic, the future of news deserts is unclear. Stites has some ideas as to how local communities could potentially emerge from a drought, with hopes the Banyon Project can lead the way, but he’s just not sure.

“I’m a fan of local news. I care deeply about it and its connection with its readers,” Mathews said. “I don’t know what the future is.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.